In unit testing, we often want to create mocks of other parts of our app in order to better isolate the particular component under test, and prevent us from dragging the whole dependency graph into our simple little unit test.

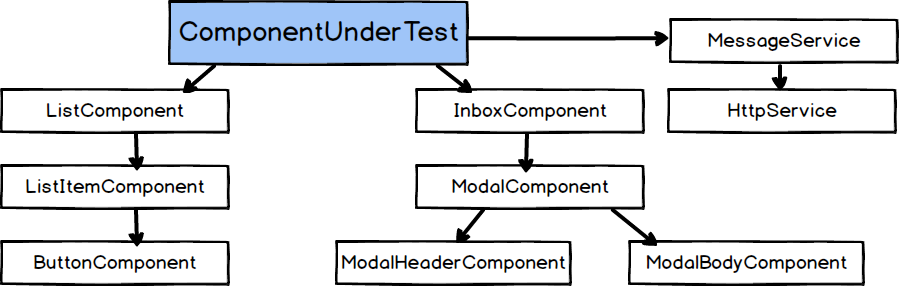

Dependency graph of a component we want to test

In the example above, we could mock out ListComponent, InboxComponent and MessageService and thereby forego the

need to pull in all of the transitive dependencies (dependencies of dependencies). Things become a bit more manageable:

Mocking immediate dependencies of the component under test

But a big problem with mocking is duplicated code. More code == more to maintain. When, at some future time, we update the real component, we need to remember to update the mocks. Failure to do so leaves us with stale mocks, festering like bad apples in our code base. The rot spreads to our tests, which no longer assure us of correctness; on the contrary, we are now explicitly testing for incorrect behaviour.

Can we make use of TypeScript to ensure that we avoid the stale mocks problem?

Let’s take a look at some solutions you might try:

Solution 1: Code to Interfaces

One solution is to create an interface which describes the public API of our component. The component and the mock can then both implement this interface. Changes to the component API would require one to update the interface, which in turn would raise TypeScript compiler errors if we fail to update the mock.

interface ListComponentInterface {

getFilteredList: () => string[];

}

class ListComponent implements ListComponentInterface {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... snip

}

}

class MockListComponent implements ListComponentInterface {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... mock snip

}

}

The obvious drawback is that now you have to maintain both the interface and the implementation. Too much overhead. Next!

Solution 2: The Mock Implements the Real Component

Did you know you can do this in TypeScript?

class ListComponent {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... snip

}

}

class MockListComponent implements ListComponent {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... mock snip

}

}

Pretty cool huh? The problem is that this breaks down as soon as

ListComponent has any private members. Which is probably close to 100% of the time. Ok, what next?

Solution 3: Mapped Types to the Rescue!

From this GitHub comment I learned that we can get the benefit of implementing a class even if it has private members by using mapped types:

type PublicInterfaceOf<Class> = {

[Member in keyof Class]: Class[Member];

}

class ListComponent {

private itemCount: number;

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... snip

}

}

class MockListComponent implements PublicInterfaceOf<ListComponent> {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... mock snip

}

}

This works because mapped types do not include private or protected members. Cool!

So we have here solution which gives us type-safe mocks without the overhead of needing to maintain interfaces for all our components. There is, however, still a potential pain point with this approach: sometimes you just don’t want to have to mock all the members of a class. For example, in frameworks such as Angular, a component or service may contain lifecycle methods - public methods which exist as mere as hooks for the framework itself. Usually these are not relevent to our mocks and having to write stubs for them could get to be a pain.

To fix this issue, we’ll need TypeScript 2.8 which introduces conditional types.

If you’re not familiar with what conditional types are all about, take a bit of time to read the docs linked above, and I’d also highly recommend you watch this section of Anders Hejlsberg’s keynote at the recent TSConf where he explains them very nicely.

In short, conditional types open up a whole new world of expressiveness (and, admittedly, complexity) from TypeScript’s type system.

Solution 4: Mapped and Conditional Types

If you are new to TypeScript of have not poked around with it too deeply, the following may seem rather esoteric. With this in mind, I’ll take things step-by-step.

To reiterate, we want the benefit of the mapped type “public interface” approach, but we want to strip out the

irrelevant framework methods. In the case of Angular, these would be ngOnInit, ngOnChanges, ngOnDestroy and so on.

Let’s imagine that our ListComponent is an Angular component which happens to rely on a few of the Angular lifecycle hooks:

class ListComponent {

itemCount: number;

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... snip

}

ngOnInit() {

// ... do some init stuff, innit?

}

ngOnChanges() {

// ... react to changes

}

ngOnDestroy() {

// ... clean up all those setTimeout timers

// which somehow seem to just make UI code work

// for some disturbingly unknown reason

}

}

We will define a type which comprises a union of all the names of the lifecycle methods which we want to ignore in our mocks:

type LifecycleMethods = 'ngOnInit' | 'ngOnChanges' | 'ngOnDestroy'; // etc.

Now the conditional type magic comes into play. Here’s we want to do (in pseudo-TypeScript):

type MockOf<Class> = {

[Member in "public members of Class which aren't one of the LifecycleMethods"]: Class[Member];

}

As you may have guessed, conditional types allow us to express this concept. The new pre-defined type Exclude is defined as:

Exclude<T, U>– Exclude fromTthose types that are assignable toU.

For example:

type T1 = Exclude<string | number | boolean, number>; // string | boolean

type T2 = Exclude<'a' | 'b' | 'c' | 'd', 'a' | 'c'>; // 'b' | 'd'

Let’s use Exclude in our mapped type to give us an interface of all public, non-lifecycle members of our ListComponent:

type MockOf<Class> = {

[Member in Exclude<keyof Class, LifecycleMethods>]: Class[Member];

};

class MockListComponent implements MockOf<ListComponent> {

getFilteredList(): string[] {

// ... mock snip

}

}

And there we have it! Concise, type-safe mocks which stay fresh and tasty. As a caveat, it must be noted that since Angular doesn’t yet support TypeScript 2.8 at the time of this writing, I’ve not actually used this technique in my actual tests.

By the way, if you’re an Angular developer and find the subject of manually writing mocks to be massive a pain in the bum, I’ve written a proposal for a hugely pleasanter mocking experience. Check it out and upvote it if it seems like a sensible idea to you too. Cheers!

General Solution

To round up, here’s a full listing of a general mocking solution for TypeScript 2.8 and above:

/**

* This is the class we want to mock. It includes a mix of private and public members,

* including some public members that we don't care about for the purposes of our mock.

*/

class MyClass {

unimportantField: number;

private someInternalState: string;

constructor(banana: BananaWithGorillaAndJungle) {

banana.peel();

}

importantMethod(input: string): string {

// important stuff that we'd like to stub when it comes to testing

return 'a real string';

}

unimportantMethod(): void {

// does something or other

}

private privateMethod(): void {

// we don't care about this at all

}

}

/**

* The MockOf type takes a class and an optional union of

* public members which we don't want to have to implement in

* our mock.

*/

type MockOf<Class, Omit extends keyof Class = never> = {

[Member in Exclude<keyof Class, Omit>]: Class[Member];

}

/**

* Our mock need only implement the members we need. Note that even the omitted members

* are still type-safe: changing the name of "unimportantField" in MyClass will

* result in a compiler error in the mock.

*/

class MockMyClass implements MockOf<MyClass, 'unimportantField' | 'unimportantMethod'> {

importantMethod(input: string): string {

return 'a test string';

}

}